Boethius

Boethius teaching his students (initial in a 1385 Italian manuscript of the Consolation of Philosophy.) |

|

| Full name | Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius |

|---|---|

| Born | Rome 480 AD |

| Died | Pavia 524/5 AD |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| Main interests | problem of universals, religion, music |

| Notable ideas | The Wheel of Fortune |

Anicius Manlius Severinus Boëthius,[1][2][3] commonly called Boethius (ca. 480–524 or 525) was a Christian philosopher of the early 6th century. He was born in Rome to an ancient and important family which included emperors Petronius Maximus and Olybrius and many consuls.[3] His father, Flavius Manlius Boethius, was consul in 487 after Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman Emperor. Boethius, of the noble Anicius lineage, entered public life at a young age and was already a senator by the age of 25.[4] Boethius himself was consul in 510 in the kingdom of the Ostrogoths. In 522 he saw his two sons become consuls.[5] Boethius was executed by King Theodoric the Great,[6] who suspected him of conspiring with the Byzantine Empire. It may be possible to link his work to the game of Rithmomachia.

Contents |

Early life

Boethius' exact birth date is unknown.[3] It is generally established at around 481, the same year of birth as Benedict of Nursia. Boethius was born to a patrician family which had been Christian for about a century. His father Manlius Boethius' line included two popes, and both parents counted Roman emperors among their ancestors.

Although Boethius is believed to have been born into a Christian family, some scholars have conjectured that he abandoned Christianity for paganism, perhaps on his deathbed.[7] Momigliano argues "many people have turned to Christianity for consolation. Boethius turned to paganism. His Christianity collapsed — it collapsed so thoroughly that perhaps he did not even notice its disappearance." [8] However, this has been a popular idea among scholars of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and does not reflect the majority of scholarship on the matter.[9] It is unknown where Boethius received his formidable education in Greek. Historical documents are ambiguous on the subject, but Boethius may have studied in Athens, and perhaps Alexandria.[10] Since the elder Boethius is recorded as proctor of a school in Alexandria circa 470, the younger Boethius may have received some grounding in the classics from his father or a close relative.

As a result of his education and experience, Boethius entered the service of Theodoric the Great, who in 506 had written him a graceful and complimentary letter about his studies. Theodoric subsequently commissioned the young Boethius to perform many roles.

Late life

In 522 his two sons, Symmachus and Boethius, received the high honour of being appointed joint consuls; that same year, Boethius accepted the appointment to the position of magister officiorum, the head of all the government and court services.[10] Also in 520, Boethius was working to revitalize the relationship between the Church in Rome and the Church in Constantinople. This may have led to loss of favour.[10]

In 523, however, Theodoric ordered Boethius arrested on charges of treason, possibly for a suspected plot with the Byzantine Emperor Justin I, whose religious orthodoxy (in contrast to Theodoric's Arian opinions) increased their political rivalry.[10] Boethius himself attributes his arrest to the slander of his rivals. Theodoric was feeling threatened by events, however, and several other leading members of the landed elite were arrested and executed at about the same time. Also, because of his previous ties to Theodahad, Boethius apparently found himself on the wrong side in the succession dispute following the untimely death of Eutharic, Theodoric's announced heir. Whatever the cause, Boethius found himself stripped of his title and wealth and imprisoned at Pavia, where he was executed the following year.[5] Boethius was executed at the young age of 44 years on October 23, 524.[4] The method of his execution varies in the sources; he was perhaps killed with an axe or a sword, or was clubbed to death. His remains were entombed in the church of San Pietro in Ciel d'Oro in Pavia. In Dante's Paradise of The Divine Comedy, the spirit of Boethius is pointed out by St. Thomas Aquinas:

- Now if thy mental eye conducted be

- From light to light as I resound their frame,

- The eighth well worth attention thou wilt see.

- The soul who pointed out the world's dark ways,

- To all who listen, its deceits unfolding.

- Beneath in Cieldauro lies the frame

- Whence it was driven; from woe and exile to

- This fair abode of peace and bliss it came.[11]

Works

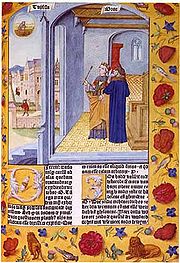

Boethius's best known work is the Consolation of Philosophy (De consolatione philosophiae), which he wrote most likely while in exile under house arrest or in prison while awaiting his execution, but his lifelong project was a deliberate attempt to preserve ancient classical knowledge, particularly philosophy.[12] This work represented an imaginary dialogue between himself and philosophy, with philosophy being personified by a woman.[12] The book argues that despite the apparent inequality of the world, there is, in Platonic fashion, a higher power and everything else is secondary to that divine Providence.[6] There are several manuscripts that have survived and been expansively edited, translated and printed throughout the late 15th century and forward in Europe.[12] He intended to translate all the works of Aristotle and Plato from the original Greek into Latin.[13] His completed translations of Aristotle's works on logic were the only significant portions of Aristotle available in Europe until the 12th century. However, some of his translations (such as his treatment of the topoi in The Topics) were mixed with his own commentary, which reflected both Aristotelian and Platonic concepts.[12] Boethius planned to completely translate Plato's Dialogues, but there is no known surviving translation, if it was actually ever begun.[14] A contemporary of Boethius, Marcus Aurelius Cassiodorus, was a Calabrian born in Scyllacium.[4]

Boethius intended to pass on the great Greco-Roman culture to future generations by writing manuals on music and astronomy, geometry, and arithmetic.[4]

Several of Boethius' writings, which were largely influential during the Middle Ages, drew from the thinking of Porphyry and Iamblichus.[15] Boethius wrote a commentary on the Isagoge by Porphyry,[16] which highlighted the existence of the problem of universals: whether these concepts are subsistent entities which would exist whether anyone thought of them, or whether they only exist as ideas. This topic concerning the ontological nature of universal ideas was one of the most vocal controversies in medieval philosophy.

Besides these advanced philosophical works, Boethius is also reported to have translated important Greek texts for the topics of the quadrivium [14] His loose translation of Nicomachus's treatise on arithmetic (De institutione arithmetica libri duo) and his textbook on music (De institutione musica libri quinque, unfinished) contributed to medieval education.[16] De arithmetica, begins with modular arithmetic, such as even and odd, evenly-even, evenly-odd, and oddly-even. He then turns to unpredicted complexity by categorizing numbers and parts of numbers.[17] His translations of Euclid on geometry and Ptolemy on astronomy,[18] if they were completed, no longer survive. Boethius made Latin translations of Aristotle's De interpretation and Categories with commentaries. These were widely used during the Middle Ages.[10]

Boethius' De institutione musica, was one of the first musical works to be printed in Venice between the years of 1491 and 1492. It was written toward the beginning of the sixth century and helped medieval authors during the ninth century understand Greek music.[19]

In his "De Musica", Boethius introduced the fourfold classification of music:

- Musica mundana — music of the spheres/world

- Musica humana — harmony of human body and spiritual harmony

- Musica instrumentalis — instrumental music (incl. human voice)

- Musica divina — music of the gods

During the Middle Ages, Boethius was connected to several texts that were used to teach liberal arts. Although he did not address the subject of trivium, he did write many treatises explaining the principles of rhetoric, grammar, and logic. During the Middle Ages, his works of these disciplines were commonly used when studying the three elementary arts.[18]

Cassiodorus' biography of Boethius authorized that Boethius wrote about theology, composed a pastoral poem, and was most famous for his ability to translate works of Greek mathematics and logic.[20] Boethius also wrote Christian theological treatises, which generally supported the orthodox position against Arianism and other dissident forms of Christianity.[21] These included On the Trinity, One the Catholic Faith, and a Book against Eutychius and Nestorius. ,[15]

Lorenzo Valla described Boethius as the last of the Romans and the first of the scholastic philosophers.[5] Despite the use of his mathematical texts in the early universities, it is his final work, the Consolation of Philosophy, that assured his legacy in the Middle Ages and beyond. This work is cast as a dialogue between Boethius himself, at first bitter and despairing over his imprisonment, and the spirit of philosophy, depicted as a woman of wisdom and compassion. "Alternately composed in prose and verse,[15] the Consolation teaches acceptance of hardship in a spirit of philosophical detachment from misfortune." [22] Parts of the work are reminiscent of the Socratic method of Plato's dialogues, as the spirit of philosophy questions Boethius and challenges his emotional reactions to adversity. The work was translated into Old English by King Alfred, and into later English by Chaucer and Queen Elizabeth;[21] many manuscripts survive and it was extensively edited, translated and printed throughout Europe from the 14th century onwards.[23] Many commentaries on it were compiled and it has been one of the most influential books in European culture. No complete bibliography has ever been assembled but it would run into thousands of items.[22] "The Boethian Wheel" is a model for Boethius' belief that history is a wheel,[24] that Boethius uses frequently in the Consolation; it remained very popular throughout the Middle Ages, and is still often seen today. As the wheel turns those that have power and wealth will turn to dust; men may rise from poverty and hunger to greatness, while those who are great may fall with the turn of the wheel. It was represented in the Middle Ages in many relics of art depicting the rise and fall of man. Descriptions of "The Boethian Wheel" can be found in the literature of the Middle Ages from the Romance of the Rose to Chaucer.[25]

Veneration

Boethius is traditionally recognized as a saint by the Catholic Church because it has been thought since the early Middle Ages that he died in some respects a martyr for his maintenance of Catholicism against the Arian Theodoric.[16] His feast day is October 23. Pope Benedict XVI explains the relevance of Boethius to modern day Christians by linking his teachings to an understanding of Providence.[26]

Cultural references

Boethius figures prominently in the worldview and philosophical musings of fictional character Ignatius J. Reilly in A Confederacy of Dunces, a novel by John Kennedy Toole. Christopher Eccleston quotes a passage from Consolation of Philosophy during a brief cameo as a homeless man in the movie 24 Hour Party People.

In Chapter 27 of The Screwtape Letters, C.S. Lewis holds Boethius up as an example of timeless wisdom—a "meddlesome" writer, according to his morally inverted character Uncle Screwtape.

Notes

- ↑ ""Boethius" has four syllables, the o and e are pronounced separately. It is hence traditionally written with a diæresis, viz. "Boëthius", a spelling which has been disappearing due to the limitations of typewriters and word processors."

- ↑ The name Anicius demonstrated his connection with a noble family of the Lower Empire, while Manlius claims lineage from the Manlii Torquati of the Republic. The name Severinus was given to him in honour of Severinus of Noricum.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hodgkin, Thomas. Italy and Her Invaders. London: Adamant Media Corporation, 2001.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 General Audience of Pope Benedict XVI, Boethius and Cassiodorus. Internet. Available from http://www.vatican.va/holy_father/benedict_xvi/audiences/2008/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20080312_en.html; accessed November 4, 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. The Theological Tractates and The Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by H.F. Steward and E.K. Rand. Cambridge: The Project Gutenberg, 2004.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 The Online Library of Liberty, Boethius. Internet. Available from http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.phpoption=com_content&task=view&id=215&Itemid=269; accessed November 3, 2009.

- ↑ Georgetown University, Boethius. Internet. Available from http://www9.georgetown.edu/faculty/jod/Boethius.html; accessed November 6, 2009.

- ↑ Momigliano A., ed. The Conflict Between Paganism and Christianity in the Fourth Century.Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1963.

- ↑ P.G. Walsh, in the introduction to Boethius' The Consolation of Philosophy (Oxford: Oxford U. Press, 2000) xxvii

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 MacTutor History of Mathematicas archive, Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius. Internet. Available from http://www-history.mcs.standrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Boethius.html; accessed November 4, 2009.

- ↑ Boethius. Consolation of Philosophy. Translation

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by Joel Relihan. Norton: Hackett Publishing Company, 2001.

- ↑ The Catholic Primer, The Trinity Is One God Not Three Gods. Internet. Available from http://www.hismercy.ca/content/ebooks/BoethiusAnicius%20Manlius%20Severinus%20-%20Trinity.pdf; accessed November 2, 2009.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Barnish, S.J.B. Variae, I.45.4. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1992.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Anicius Manlius SeverinusBoethius. Internet. Availablefrom http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/boethius/; accessed November 7, 2009.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2

"Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ↑ Schrader, Dorothy V. “De Arithmetica, Book I, of Boethius.” Mathematics Teacher 61 (1968):615-28.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Masi, Michael. “The Liberal Arts and Gerardus Ruffus’ Commentary on the Boethian De Arithmetica.” The Sixteenth Century Journal 10 (Summer 1979): 24.

- ↑ Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Fundamentals of Music. Translated, with Introduction and Notes by Calvin M. Bower. Edited by Claude V. Palisca. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

- ↑ James Shiel, Encyclopedia Britannica (2005), CD-ROM edition, Boethius

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by W.V. Cooper.London: J.M. Dent and Company, 1902.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus. Consolation of Philosophy. Translated by H.R. James. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide, 2007.

- ↑ Richard A. Dwyer, Boethian Fictions, Narratives in the Medieval French Versions of the Consolatio Philosophiae, Medieval Academy of America, 1976.

- ↑ Boethius, Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Victor Watts (rev. ed.), Penguin, 1999, p.24 n.1.

- ↑ The Middle Ages, The Wheel of Fortunes. Internet. Available from http://www.themiddleages.net/wheel_of_fortune.html; accessed November 4, 2009.

- ↑ General Audience of Pope Benedict XVI, 12 March 2008

References

- James, H. R. (translator) [1897] (2007), The Consolation of Philosophy of Boethius, The University of Adelaide: eBooks @ Adelaide, http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/b/boethius/.

- Marenbon, John (2004). Boethius. Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-513407-9. OCLC 191826140 223148558 231973258 50143461 51107445 57459204 63294098 186379876 191826140 223148558 231973258 50143461 51107445 57459204 63294098.

- Colish, Marcia L. (2002). Medieval foundations of the Western intellectual tradition, 400-1400. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-07852-8. OCLC 40752272 52583412 185694056 40752272 52583412.

- Chadwick, Henry (1981). Boethius, the consolations of music, logic, theology, and philosophy. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-826549-2. OCLC 8533668.

- Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus (1867). "Boetii De institutione arithmetica libri duo". In Gottfried Friedlein (in Latin). Anicii Manlii Torquati Severini Boetii De institutione arithmetica libri duo: De institutione musica libri quinque. Accedit geometria quae fertur Boetii. in aedibus B.G. Teubneri. pp. 1–173. http://books.google.com/books?id=VwS0VRBsJLgC&printsec=titlepage&source=gbs_summary_r&cad=0#PPA1,M1. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus (1867). "Boetii De institutione musica libri quinque". In Gottfried Friedlein (in Latin). Anicii Manlii Torquati Severini Boetii De institutione arithmetica libri duo: De institutione musica libri quinque. Accedit geometria quae fertur Boetii. in aedibus B.G. Teubneri. pp. 177–371. http://books.google.com/books?id=VwS0VRBsJLgC&printsec=titlepage&source=gbs_summary_r&cad=0#PRA1-PA177,M1. Retrieved 2008-08-03.

- John, Donald Attwater; Catherine Rachel (1995). The Penguin dictionary of saints. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-140-51312-4. OCLC 34361179.

- Baird, Forrest E.; Walter Kaufmann (2008). From Plato to Derrida. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-158591-6.

- Heather, Peter (1996). The Goths. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Marenbon, John (ed.) (2009). The Cambridge Companion to Boethius Cambridge University Press.

Discography

- Carlo Forlivesi, Boethius (2008) for biwa. The piece is included in the CD album SILENZIOSA LUNA (ALCD 76).

External links

Works

- (English) Works by Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius at Project Gutenberg

- (English) De Musica — Boethius

- (English) De Trinitate (On the Holy Trinity) — Boethius

- A 10th century manuscript of Institutio Arithmetica is available online from Lund University, Sweden

- The Geoffrey Freudlin 1885 edition of the Arithmetica, from the Cornell Library Historical Mathematics Monographs

On Boethius

- Blessed Severinus Boethius at Patron Saints Index

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Boethius", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Boethius.html.

- Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius entry by John Marenbon in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Contribution of Boethius to the Development of Medieval Logic

- Boethius at The Online Library of Liberty

"Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.

"Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius". Catholic Encyclopedia. 1913.- On Boethius and Cassiodorus — Pope Benedict XVI

| Preceded by Flavius Inportunus (alone) |

Consul of the Roman Empire 510 |

Succeeded by Arcadius Placidus Magnus Felix, Flavius Secundinus |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed (1913). Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.